The end of 9 to 5

13 Apr

The idea of people working regular hours is an anomaly; a blimp on the radar of human development. Celebrate it for what it was and move on.

Pascal Finette – He worked for Mozilla (Director), Ebay (Senior Manager) and Google (Portfolio Manager). Describes himself as an Entrepreneur, Speaker, Chief Heretic, Posse Leader, Nerd, Coffee Snob, Dancer-in-the-Moment. Check out his Heretic movement under heretic.me

Since the dawn of time human activity was governed by the cycle of the sun. We rose with the first sign of the sun, plowed the fields, went hunting and generally did what was necessary to sustain ourselves – until the sun set and it went dark. If the moon shone bright enough we worked through the night. Otherwise we slept. The three billion people around the world who live in poverty and don’t have access to electricity still operate by this cycle. We rested when there was less work to do, we took a break when we felt tired and work was generally „always there“.

The industrial revolution brought us a new regime: The machines demanded to be kept moving. Electricity expanded „daylight hours“ ad infinitum. We went from twelve hours in the fields to twelve hours slaving away in the newly built factories, took a break when we were told to take a break and labeled this all „progress“.

Only in the second half of the nineteenth century, with the rise of the unions and thus the (somewhat) realignment of power from employers to employees did we get the „40 hour work week“, Sunday’s off and the rhythm of nine to five. Moving from blue collar (factory floors) to white collar (offices) jobs further accelerated this trend.

This regiment stayed with us for a short hundred or so years. Starting with the advent of the digital economy – we rapidly moved back to where we came from: A culture of „always on“; a world where boundaries between work and personal life blur and where we work, once again, from dusk till dawn (and longer); resting when there is less work to do (or not at all) and taking breaks when we feel tired (or never) and with work just always being there.

The „new economy“, a term coined during the first dot-com boom in the late nineties, promised a future where we live as free agents, do our work from coffee shops or hip offices; where work feels like play and play becomes life. The reality saw us working endless hours, our heads illuminated by the blue glare of our computer screens and our desires fueled by the promised payoff of untold riches through a public stock offering of our companies. Nine to five became a forbidden term – the word you used to describe your colleagues who „didn’t have their priorities right“ and „didn’t pull their weight“.

We rewired our brains for the instant dopamine rush we get when an email hits our inbox. The fear of missing out became „a thing“. When RIM introduced their first Blackberry devices, which we proudly wore on our belts and which vibrated with each and every email which came into our inboxes, we were hooked. We developed „phantom vibration syndrome“ when we didn’t have our Blackberrys with us. With the advent of Apple’s iPhone, iPad and Google’s Android devices we started begging our companies to allow us to bring our own devices to work (a trend which got its own acronym: BYOD). And in return are always online, always checking email, never switching off anymore.

We happily bartered our right to work five days a week from nine to five for a world of instant gratification and constant rush. Probably we were never meant to put a clean border between work and life.

Now excuse me: I need to check my email, update my status on Facebook and catch up on the latest news on Twitter.

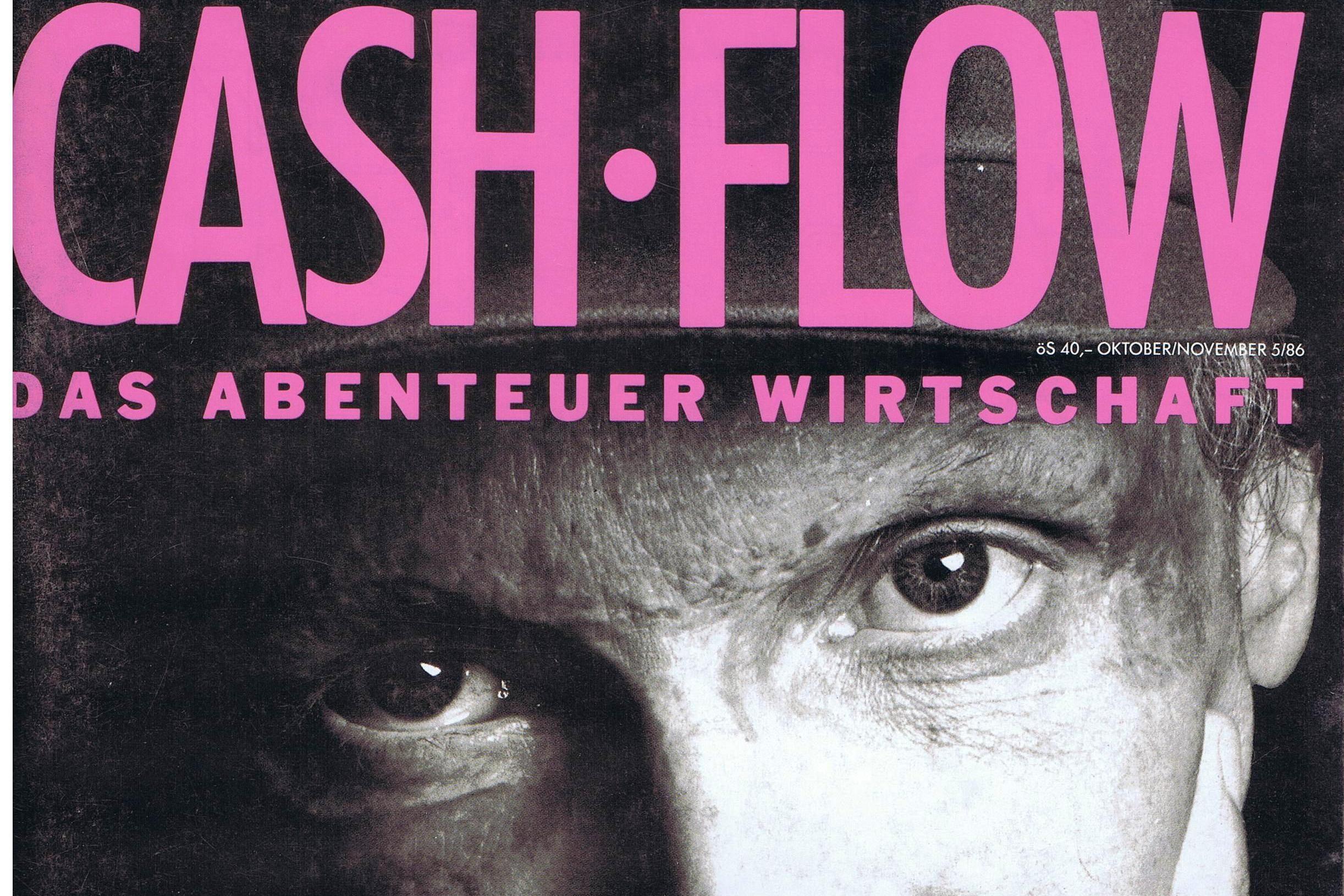

NEU: CASH FLOW 01-2015 Vienna Special

NEU: CASH FLOW 01-2015 Vienna Special